iSearching

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Third and final questionnaire

Questionnaire 3

|

| Image by Satane |

Made it!

1. Take some time to think about your topic. Now write down what you know about it.

Inquiry based learning with year 3 students undertaking historical research:

· Needs to be approached from narratives as children naturally relate to the stories of others and can more easily relate their understandings in story form to others.

· Should start with the bigger concepts like change so that children won’t just be focused on acquiring and memorising facts. This is a concept based approach. The teacher can help the students to formulate questions to guide them in their searching. In this way the learning is child-centred and will enable a deeper level of meaning to be attained.

· Should be a guided process. It is critical for the teacher to provide intervention along the way to enable the students to keep moving forward to find answers to their questions.

· The Inquiry based learning activity should provide opportunities for students to share their work with one another and provide feedback to help each other with the task. Students who work collaboratively in this way learn a great deal more than in an individual task but the right guidance and intervention by the teacher is imperative in this process.

2. How interested are you in this topic? A great deal

3. How much do you know about this topic? Quite a bit

4. Thinking back on your research project, what did you find easiest to do? Please list as many things as you like.

· In the final stages of the inquiry I can now reflect and identify that it became easier once I had clarified and formulated a focus for my search. That wasn’t particularly easy to do but after that I felt that I had direction and a real purpose.

5. Thinking back on your research project, what did you find most difficult to do? Please list as many things as you like.

· I found it difficult to keep track of the information I collected. I really lacked a system of organisation and at the end I wished I’d had one.

· I found it difficult to get past the stage of formulating my focus. I seemed to be searching aimlessly for information for a long time and this created confusion and frustration.

· I found it difficult to start!

6. What did you learn in doing this research project? Please list as many things as you like.

· In researching this topic, I have personally learnt the value of reflection and evaluation at each stage of the inquiry process. This will help me to be more aware of the way in which I can support students and intervene with strategies to help them.

· This type of questionnaire is very useful to use with children. It helps to identify what they know at the outset of the research and to keep track of their progress as the unit evolves. It would be a useful tool when trying to identify intervention strategies that would be most beneficial to students to keep them moving with their inquiry.

· I have come to truly appreciate the value of inquiry-based learning. It is student focused and a far more motivating and engaging way for students to learn. It personalises the learning and provides the approach to differentiate student learning to suit the needs of the learner.

· In doing the research project, I have gained more confidence in using inquiry learning. I feel more capable of implementing inquiry based units with students and adapting information literacy models to suit students.

· This project has also given me the confidence to promote inquiry based learning with colleagues and to be able to provide the support for classroom teachers in implementing inquiry units with their classes.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Reflection about feedback given

|

| Image by Sea-turtle The unexpected lessons from this step in the process! |

My first response (I will bravely admit!) to the thought of receiving feedback from my peers AND then having to make changes to what I thought I had worked enough on was not worth repeating! However, as I took those first steps and started to read their essays I discovered that there were other ways to approach the essay. I found that I had used things or had learnt things that may be useful to share with them. I couldn't wait to see what they would think of my "attempt" (I had acknowledged now that it was a draft and not the final version). For the first time I was looking critically at the content and structure of my peer's essays and it was triggering the same reflections about my own work.

Once my feedback was received, I was able to see my essay from the perspective of someone else's eyes. Suggestions such as, "Could the sentence be reworded to put the emphasis on the negotiated nature of the assessment item?" and "Is there a need here to talk about evaluation and reflection?" forced me to read my work through the eyes of my audience. Without the prompt, I would not have realised that the meaning could be enhanced by these changes. Questions by my colleagues enabled me to change the order of my paragraphs as they queried the importance of some points ahead of others and the logical flow of ideas.

When reflecting upon this process I can now see that I benefitted not only from receiving the feedback but also in giving the feedback too. This was a very valuable part of the process for me and one that would be often overlooked at the end of an inquiry. The effect of feedback from and to the learning community is very powerful and some of the advantages that I can identify from it are:

- Increased understandings

- Knowledge base increased

- New knowledge constructed

- Own work is viewed from a different perspective

- Collaborative skills enhanced

- Sharing of knowledge and skills with others

- Fostered critical thinking

- Developed deep learning

- Helped identify further questions and problems to solve

This process would also be valuable with children and would need to be modelled to students and gradually built upon from year to year. We need to teach our children to think critically and collaborate with one another. To collaborate and learn from one another is a life long learning skill.

Models of Information Literacy

Square Peg, Round Hole?

There are an abundance of models that attempt to outline the process of information learning for teachers and students to follow that can support inquiry based learning. They can be broadly classified into two groups, those that reflect a linear process of inquiry and those that are non-linear and are more cyclical in nature. The linear models are usually characterised by a set of steps or stages that are undertaken in a certain order, one after the other. The cyclical type models are a series of stages or phases that the inquirer works through but it is often characterised by 'a returning to' previous stages throughout the process as required.

Earlier in the blog I have explained that I could relate well to the early stages of Kuhlthau's model of the Information Search Process (ISP), notably the stages of Initiation, Selection, Exploration and Formulation. The feelings experienced at each of these phases resonated well with me. Alberta Inquiry Model (2004), illustrated below, is another model that I feel closely aligns with the inquiry process that I have undertaken. It allows for the revisiting of the various stages over and over again in the process of inquiry. I was continually looping backwards and forwards as I found new information, re-organised information, changed focus and attempted to make sense of the information. To do this constant "revisiting of the stages, I was reflecting upon the process every step of the way. Reflection and evaluation is not something that you can tag on at the end, these are processes that are happening all the time as you are synthesising new information with existing information. I believe that reflection is an integral part of each and every phase of the cycle. The flexibility that encompasses this model enables me to feel that it is OK to have some individuality in the way that I undertake the information learning process.

The Alberta Inquiry Model

I also believe that you'll never fully get it right and that at the end of the "completed" product there needs to be a process of evaluation, not only of the finished product but of the process itself and what I have learned about myself as an inquirer. For me, one of the biggest lessons that I will take from the process is to find a way to be more systematic with the collection of information. Throughout the process of searching I found valuable information and then couldn't relocate it again or if I could there was a lengthy search for it. This obviously caused much frustration and contributed to a lot of time wastage. Kuhlthau identifies several concepts for the use of information once it has been collected. One of these is 'Managing Inquiry: Keeping track along the way' (2007, p89). These can include strategies for note-taking either in a written journal or via tools on the computer to record sources of information. In subsequent searches I will seek help to further refine these skills so that the process does not become so overwhelming.

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Information Literacy and the GeST windows

|

| Image from ehoyer's photostream |

Information literate learners are able to access, process, organise, create and present information in a range of ways that make meaning for them and all the construction of personal knowledge. Information skills must be embedded across the school curriculum and explicitly taught in the context of teaching and learning programs (2009).

However, the more I think about this statement and the deeper I delve into this area of information literacy, I believe there is more to being literate than simply accessing, selecting, collecting, organising, managing and utilising information. It is far more than the acquisition of a skill set to become highly literate. Today's 21st century learner is confronted with information in a wide variety of forms and via a variety of mediums and needs to be able to utilise the technological tools that often create access to much of this information. With this comes the need to be able to critically evaluate all sources of information and reflect upon its meaning and the way in which it changes our existing knowledge base.

Information literacy needs to be transformative; the information literacy process needs to provide opportunities for learning that will enable the learner to challenge their existing knowledge base, critically reflect on what they know and how they can incorporate new understandings and then utilise the newly constructed information to make a difference to themselves and others. Lupton and Bruce (2010) view curricula in terms of the GeST windows model. At its most basic level the Generic Window is where information literacy is viewed in terms of the acquisition of a set of skills that are unrelated to a context and that can be learnt to be used when engaging with information. The Situated Window sees information literacy as the learning and utilisation of those skills for a specific, authentic situation. Information is viewed as being part of who we are and inquiry based learning is firmly grounded here. The Transformative window encompasses the previous two windows and in addition engages the learner in practices that empower them to question the information, critique it and use it to transform their view of the world and make a difference to society.

|

| Showing the inclusive relationship of all three windows. The Transformative Window is dependent upon the other two windows. (Image from Lupton Powerpoint used in Tutorials 2011) |

I feel as though this experience of the search process has forced me to work through all three windows. At its most basic level I have learned and used the skills of database searching for a very relevant and authentic purpose, to formulate the theoretical basis of my Inquiry Learning Activity with Year Three students finding out about their local history. I have been forced to construct new understandings and incorporate the theories and models that I have encountered in the literature with my existing knowledge of teaching and learning. However this process has been far more than the acquisition of skills for the purposes of creating a blog and establishing the basis of my ILA. It has empowered me to create my own views about historical inquiry for younger students and what elements I believe are important in the process. I have been able to share these views and will share the results via a written report but I am also expressing my perspective through this blog that will reach an untold number of fellow bloggers around the world. Wow that's empowering stuff!

Evaluating information

What to use and what not to use - that is the question!

As I stated in my second Slim Toolkit Questionnaire, I was collecting articles in abundance and I was struggling to find the time to read them thoroughly and keep searching! It quickly became apparent that I needed to start sorting through those that would be useful to my context essay and come up with a system by which I could select articles more accurately. A tutorial at around this time had included a discussion about the things to look for when evaluating the worth of an article for inclusion in your research. Kuhlthau (2007) identifies five characteristics of information that can be utilised in determining whether the article is beneficial to your inquiry or not. These five characteristics are:

- Expertise - Who the author is, their qualifications and credentials

- Accuracy - the factual correctness of the source

- Currency - the date of publication of the material

- Perspective and - the author's point of view, purpose in writing the article and any bias

- Quality - How well written and articulate the piece of writing is

So in order to consider each of these characteristics in the light of my inquiry this is how I applied them when evaluating whether or not information was to be used.

1. The author of the source in this case, needed to be connected to educational research from a university. The list of references to other experts in the area of historical inquiry was an indication of the amount of research that had been drawn upon in writing the article. The journal that it appeared in also helped give the article credibility. For example the journal, "Social Studies Research and Practice" featured articles by credible authors on the specific area of my inquiry.

2. The accuracy of the information was not as clear. I have already referred to my ability to see trends in ideas and concepts across the literature. This was one element that I utilised in determining the accuracy of the information. I felt that the literature was not always as accurate in terms of its relevance to specifically Year 3 students as it tended to encompass all the elementary years. However in the end I generalised the findings to suit the younger years.

3. Part of my search process was to only use sources that were dated from 2001 to the present day. Theories and models of inquiry had changed over the years so I felt that it was important to have recent, up to date information.

4. The point of view of the author wasn't always evident in the title but became more obvious in the first couple of paragraphs.The following article sounded as though it would be worthwhile. However upon further reading it was discarded because it was more about the National Inquiry into School History rather than the inquiry approach used in school history, as suggested in the title.

2. The accuracy of the information was not as clear. I have already referred to my ability to see trends in ideas and concepts across the literature. This was one element that I utilised in determining the accuracy of the information. I felt that the literature was not always as accurate in terms of its relevance to specifically Year 3 students as it tended to encompass all the elementary years. However in the end I generalised the findings to suit the younger years.

3. Part of my search process was to only use sources that were dated from 2001 to the present day. Theories and models of inquiry had changed over the years so I felt that it was important to have recent, up to date information.

4. The point of view of the author wasn't always evident in the title but became more obvious in the first couple of paragraphs.The following article sounded as though it would be worthwhile. However upon further reading it was discarded because it was more about the National Inquiry into School History rather than the inquiry approach used in school history, as suggested in the title.

Title: 'It ain't what you do, it's the way that you do it' : the national history inquiry, SOSE and the enacted curriculum.

Personal Author: Taylor, A.

Source: Ethos 7-12; v.9 n.1 p.9-19; Term 1 2001

Abstract: In November 1999 the Commonwealth announced the establishment of a National Inquiry into School History. This article briefly outlines the process of the inquiry and its outcomes and then goes on to focus on one particular aspect of the inquiry research findings which has interesting implications for the teaching of Studies of Society and the Environment.

5. When assessing the worth of an article it was important that it was well written and well structured. Many articles that were included, cited from other works which further added to the quality and validity of the article.

The following articles were included. Both authors were assistant or associate professors and were published in academic journals that were included in an educational database. The abstracts included many of the themes and ideas that were continually surfacing in other articles as well. The information was current and relevant to the teaching of history today for younger students. Whilst the second article was presented from research based around pre-service teachers and their approach to teaching inquiry-based history the findings were still relevant.

Teaching Elementary Students How to Interpret the Past. By: Fertig, Gary. Social Studies, v96 n1 p2 Jan-Feb 2005. (EJ712159)

Elementary students can learn how to take an interpretive approach to learning history so that they can construct knowledge about collective past experience in ways that provide a meaningful context for understanding present experience. Like historians, children communicate their interpretations to others by telling or writing stories in which they "do not discover the past so much as they create it; they choose the events and people that they think constitute the past, and they decide what about them is important to know." The stories or historical narrative accounts are selective for practical and personal reasons. They are practical because it is impossible for anyone to know or gain access to all of the facts surrounding an event, and personal because an individual's life experiences, beliefs, and values influence the choice of phenomena and ways in which that person assigns causality and significance to events. Historical narratives and the sources of evidence relied on to create them require interpretation because they are inherently selective, incomplete, and value based. This article discusses why it is important to teach children to interpret the past and challenges to interpreting the past with children. Suggested activities for teaching elementary students how to interpret the past are appended.

5. When assessing the worth of an article it was important that it was well written and well structured. Many articles that were included, cited from other works which further added to the quality and validity of the article.

The following articles were included. Both authors were assistant or associate professors and were published in academic journals that were included in an educational database. The abstracts included many of the themes and ideas that were continually surfacing in other articles as well. The information was current and relevant to the teaching of history today for younger students. Whilst the second article was presented from research based around pre-service teachers and their approach to teaching inquiry-based history the findings were still relevant.

Teaching Elementary Students How to Interpret the Past. By: Fertig, Gary. Social Studies, v96 n1 p2 Jan-Feb 2005. (EJ712159)

Elementary students can learn how to take an interpretive approach to learning history so that they can construct knowledge about collective past experience in ways that provide a meaningful context for understanding present experience. Like historians, children communicate their interpretations to others by telling or writing stories in which they "do not discover the past so much as they create it; they choose the events and people that they think constitute the past, and they decide what about them is important to know." The stories or historical narrative accounts are selective for practical and personal reasons. They are practical because it is impossible for anyone to know or gain access to all of the facts surrounding an event, and personal because an individual's life experiences, beliefs, and values influence the choice of phenomena and ways in which that person assigns causality and significance to events. Historical narratives and the sources of evidence relied on to create them require interpretation because they are inherently selective, incomplete, and value based. This article discusses why it is important to teach children to interpret the past and challenges to interpreting the past with children. Suggested activities for teaching elementary students how to interpret the past are appended.

Subjects: Historians; Concept Formation; Elementary School Students; Historical Interpretation; History Instruction; Teaching Methods; Class Activities

Historical Inquiry in a Methods Classroom: Examining Our Beliefs and Shedding Our Old Ways. By: Fragnoli, Kristi. Social Studies, v96 n6 p247-251 Nov-Dec 2005. (EJ744196)

Historical inquiry is a multifaceted phenomenon. S. G. Grant describes it as "the passion for pulling ideas apart and putting them back together" (2000, 196). Historical inquiry as an instructional strategy benefits students and the classroom dynamic. It promotes students' appreciation of their personal histories while they are exploring others' histories. Students are more engaged in the subject than they would be in a class in which the teacher requires only rote memorization of minute facts. According to Levstik and Barton (1997), the memorization of isolated facts rarely advances students' conceptual understanding. The study that is reported in this article concerns the way in which preservice teachers negotiate historical inquiry-based teaching and learning in relation to their preexisting conceptions of social studies as a discipline. Another concern was finding whether having an understanding of historical inquiry influences pedagogy.

Historical inquiry is a multifaceted phenomenon. S. G. Grant describes it as "the passion for pulling ideas apart and putting them back together" (2000, 196). Historical inquiry as an instructional strategy benefits students and the classroom dynamic. It promotes students' appreciation of their personal histories while they are exploring others' histories. Students are more engaged in the subject than they would be in a class in which the teacher requires only rote memorization of minute facts. According to Levstik and Barton (1997), the memorization of isolated facts rarely advances students' conceptual understanding. The study that is reported in this article concerns the way in which preservice teachers negotiate historical inquiry-based teaching and learning in relation to their preexisting conceptions of social studies as a discipline. Another concern was finding whether having an understanding of historical inquiry influences pedagogy.

Subjects: Teaching Methods; Preservice Teachers; Student Attitudes; Social Studies; History; Inquiry; Preservice Teacher Education; Methods Courses; Case Studies; Student Surveys

Finally, the mind map that I had developed (See blog entry for Thursday August 11) proved to be a valuable tool as I began to sort the information that I collected. The articles that supported the theories and concepts that I had identified as recurring and supportive of the ILA were put aside for further reading. As my case was strengthening with support information I was able to begin making connections between pieces of information that started out as separate points. For example, the use of artifacts, object-based inquiry and the use of concrete objects in historical inquiry evolved into one point concerning the importance of basing the ILA around the use of primary sources.

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Proquest Search Explained

The picture becomes clearer after 25 seconds

Click on the screen to enlarge view

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Middle reflection questionnaire

Questionnaire 2

1. Take some time to think about your topic. Now write down what you know about it.

· That inquiry learning in history is a natural way for students to enagage with historical knowledge and understandings rather than simply acquiring facts.

· However in practice this is not what is always undertaken. Inquiry based learning as an approach is not often used by teachers in the classroom.

· An emphasis on Inquiry is proposed by the new Australian History curriculum

· There is minimal information about inquiry based learning in history or social studies for early years students

· When inquiry is used with children it needs to be guided by the teacher to ensure that they are working towards a deeper level of understanding. Appropriate questioning can be one vehicle to help them move forward and teaching them relevant skills to search, collect, organise and understand information.

2. How interested are you in this topic? Quite a bit

3. How much do you know about this topic? Quite a bit

4. Thinking of your research so far - what did you find easy to do? Please list as many things as you like.

· Once I started to research using the databases I became more confident. I started to build up lots of resources

· I began to explore different ways of searching, using a variety of search terms and trying different approaches. Experimenting with the limiters and filters etc

· The actual skills of using Boolean operators and managing each data base is getting easier

5. Thinking of your research so far - what did you find difficult to do? Please list as many things as you like.

· Sorting out what is really relevant to my search

· Formulating a clear focus for my essay

· The organisation of the information collected was difficult, especially as the amount grew!

· It is difficult finding material that is specific to the lower primary situation and specifically to history. Elementary and primary are sometimes too broad.

· I am not able to read everything thoroughly while I am searching so I am collecting more than I need. It seems a bit mountainous at the moment. I really don’t feel as though I am gaining a lot more knowledge about the topic as I have not had the time to really engage with the materials, I’ve been too consumed with collecting.

· It was difficult to keep track of where all my information was coming from. I started to note down on the printed documents what database it came from, but this was probably a bit too late in the search process.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Starting to focus and link ideas

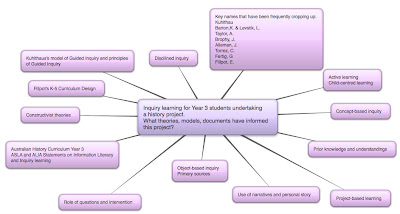

In an attempt to make sense of some of the articles that I have been collecting I have used the web2.0 tool, "Bubbl.us" to make notes of the key ideas, themes and sources that I kept encountering in my searching.

The colour coding, added in the following mind map has been an attempt to link like concepts and ideas.

This process was extremely helpful to me in trying to make sense of a huge array of information. It was the basis of the formulation of my focus. This technique would be a useful intervention tool to use with students when they are in that stage of information overload and they need some direction to make sense of all their information. Callison (2006) would support the use of tables, charts and mindmaps etc as a means of organising information and communicating your understanding of the relationships between ideas. This could also provide a valuable means of assessment of a student's level of inquiry and the evidence needed to guide the type of intervention needed to help students to move forward in their investigation.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Focus! Focus! Focus!

Since my last post I have had a few more sessions of database searching. I have used A+ and Eric. Some of these search results will be elaborated on in future blogs. However, over the past couple of days since I have started to search the databases I have found that the following things have occurred:

- I have become more confident in using search terms and Boolean operators. I have been more likely to deviate away from the step by step instructions of the demonstration videos to see if another way works or what it may bring up. In the process I have probably been taken off onto many tangents, spent way too much time there for only a few possible results and collected information that is not entirely useful. This can be over whelming at times.

- Some common themes and ideas have started to occur more frequently in some of the information that I have found. For example, the idea of historical inquiry as a disciplined inquiry; the use of artifacts and object-based inquiry when undertaking historical inquiry; and the use of narratives and personal stories as a natural way into historical inquiry for elementary students. This has helped me to distinguish between articles in terms of their usefulness if there were common themes coming through in the key points or the titles.

- I have started to form a focus for the context essay or a direction that I think it will take. I have moved on from the mere collection of information that I hope will be useful to a more purposeful collection with a vision to how it might shape my essay. This was not a straight forward process. I seemed to go backwards and forwards over the information drawing together the common themes and then returning to the outline for the essay and the elements that I thought it should contain contain. There were times when I thought it was starting to come together in my mind and then I'd come across other information that would throw my focus off course. This seemed to happen over and over again! All of this is a step forward as I try to make sense of the information and try to assimilate it with my existing knowledge and the demands of the task.

Reflections..

Upon reflection I can see that at this point in the process, my search is mirroring the third and fourth phases of Kuhlthau's Model of the Information Search Process (2007). These stages are "exploration" and "formulation."I expected that once I started searching the databases that I would find the information and then everything would start to fall into place. However instead of it being easy, I found that the information challenged my previous thinking and presented me with new theories and ideas that I struggled to make sense of, in terms of my ILA with my Year 3 group. I was confused and overwhelmed with the amount of information and how it would fit neatly into an inquiry learning model for me to follow or adapt. It wasn't going to be that easy! My struggle was with the way that I was going to utilise the various sources of information in a new cohesive way to inform my learning activity. Kuhlthau asserts that this is the stage where the real learning begins because these uncertainties drive you to find meaning. I was really struggling as a result of my uncertainty as to how I was going to connect all my new found information.

Once I identified that my focus would be to answer the question, "What are the theories, models and curriculum documents that have informed my Information Learning Activity?" I began to search more purposefully and I started to feel like I had regained some control over where I was heading.

I have also been able to identify with the early stages of Callison's model, "The Five Elements of Information Inquiry (2006). My information searching lead me to new information which in turn triggered questions and further exploration. As the trends in the information surfaced (as mentioned above) I was able to gather information that confirmed my initial ideas. This was starting to feel like the way forward and it felt safe. However when I came upon new information that identified the importance of narratives and stories as a way into historical inquiry I needed to construct new understandings for my ILA (Colby, 2008). Callison calls this element, "assimilation" where new knowledge is merged with previous understandings to form a new view or perspective. This involves reflective questioning and analysis each time new information is encountered and is thus a cyclical process encountered many times in the information search process. I feel that at this stage Callison's approach is a more accurate match for my experiences than the Kuhlthau ISP because I identify more strongly with that continuous cycle of questioning, exploring, assimilating, inferring and reflecting each time new information is encountered.

Upon reflection I can see that at this point in the process, my search is mirroring the third and fourth phases of Kuhlthau's Model of the Information Search Process (2007). These stages are "exploration" and "formulation."I expected that once I started searching the databases that I would find the information and then everything would start to fall into place. However instead of it being easy, I found that the information challenged my previous thinking and presented me with new theories and ideas that I struggled to make sense of, in terms of my ILA with my Year 3 group. I was confused and overwhelmed with the amount of information and how it would fit neatly into an inquiry learning model for me to follow or adapt. It wasn't going to be that easy! My struggle was with the way that I was going to utilise the various sources of information in a new cohesive way to inform my learning activity. Kuhlthau asserts that this is the stage where the real learning begins because these uncertainties drive you to find meaning. I was really struggling as a result of my uncertainty as to how I was going to connect all my new found information.

Once I identified that my focus would be to answer the question, "What are the theories, models and curriculum documents that have informed my Information Learning Activity?" I began to search more purposefully and I started to feel like I had regained some control over where I was heading.

I have also been able to identify with the early stages of Callison's model, "The Five Elements of Information Inquiry (2006). My information searching lead me to new information which in turn triggered questions and further exploration. As the trends in the information surfaced (as mentioned above) I was able to gather information that confirmed my initial ideas. This was starting to feel like the way forward and it felt safe. However when I came upon new information that identified the importance of narratives and stories as a way into historical inquiry I needed to construct new understandings for my ILA (Colby, 2008). Callison calls this element, "assimilation" where new knowledge is merged with previous understandings to form a new view or perspective. This involves reflective questioning and analysis each time new information is encountered and is thus a cyclical process encountered many times in the information search process. I feel that at this stage Callison's approach is a more accurate match for my experiences than the Kuhlthau ISP because I identify more strongly with that continuous cycle of questioning, exploring, assimilating, inferring and reflecting each time new information is encountered.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)